Charlotte Renaud

Arts & Culture Editor

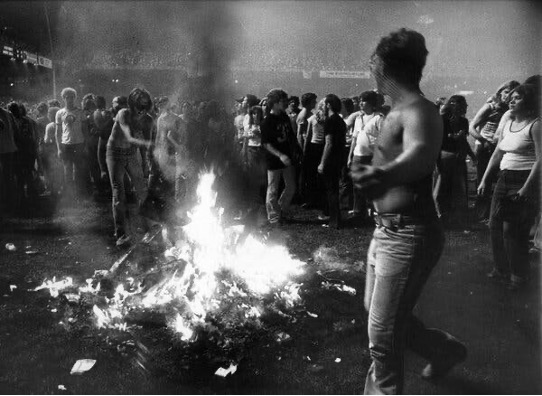

Photo via PBS

On the summer evening of July 12th 1979, a Major League Baseball (MLB) radio promotional event erupted into an anti-disco riot. The disguised attempt silenced the black and queer communities and sent shockwaves throughout the entire nation. This catalytic incident is referred to as Disco Demolition Night.

Steve Dahl, a radio personality for Chicago’s WDAI (a rock radio station) was fired from his job when the station adopted a disco format like many others at the time. Even after having found work at another radio station, Dahl’s bitterness towards disco as a genre was still very much present. He launched a “Disco Sucks” campaign and hosted “Death to Disco” rallies which appealed to his growing number of listeners, most of which aligned with his white macho character. It is in collaboration with White Sox promotions director, Mike Veeck, that they organised Disco Demolition Night.

On the night of July 12th, the Chicago White Sox and Detroit Tigers were scheduled to play a doubleheader. The game took place in the white working-class neighbourhood of Chicago’s Bridgeport Comiskey Park, which already had an anti-disco culture. The admission was 98 cents (a quarter of the regular price of a ticket) and free for those who brought a disco record with the intention of destroying it. Consequently, attendance at the event exceeded expectations, gathering over 50,000 people.

The crowd was filled with banners conveying slogans such as “Disco Sucks.” During intermission, fans threw records, firecrackers, and liquor bottles, some of which were even aimed at the players. The climax of the night took place at around 8:40 PM when Dahl, dressed in military attire, made his appearance on the field to personally set a crate filled with over fifty thousand disco records on fire with fireworks: an explosion that would be felt by the disco community throughout the nation. According to Gillian Frank, a historian who received his Ph.D. from the Department of American Studies at Brown University, events of the same sort arose that same year. In Seattle, hundreds of rock fans gathered and attacked dance floors, while anti-disco clubs grew in popularity in Detroit and in Chicago.

The negative effects of that night were felt immediately – disco radio stations switched back to rock, gigs for disco artists were harder to come by, and the Grammy awards even cancelled their new best-disco-recording category.

Vince Lawrence was a part-time usher at the baseball stadium during Disco Demolition Night and according to Alexis Petridis, a writer at The Guardian, the black teenager realised that people weren’t just bringing disco records, “but anything made by a black artist.” It calls to question that the hatred towards disco, also known as discophobia, wasn’t inherently the dislike of a music genre, but rather; it was about incentivizing anti-gay and anti-black prejudices by trying to remove these minorities from popular culture.

It calls to question that the hatred towards disco, also known as discophobia, wasn’t inherently the dislike of a music genre, but rather; it was about incentivizing anti-gay and anti-black prejudices by trying to remove these minorities from popular culture.

Disco originated in gay dance clubs in the early 70s and was predominantly created and enjoyed by the Black, Latino, and gay communities. It offered these groups an outlet where they could express themselves and relate to something during a time where the dominant culture forbade that. Popular songs like Aretha Franklin’s “Respect” and the Pointer Sisters’ “Yes We Can” became symbols of reaffirming gay pride. Consequently, it allowed members of these minorities who owned discotheques or who created music of their own to gain respect within the industry. Disco then grew into a popular genre that appealed to the mainstream especially after the release of the movie “Saturday Night Fever” featuring John Travolta, as well as the opening of Studio 54 in Manhattan (a liberating atmosphere for sexual expression and drugs).

Not only was disco a vessel for celebration, but most importantly it was encouraging political change. Disco became a platform that increased the visibility of minorities in mainstream culture, which further encouraged gay political activism and the fight for civil rights in America. Disco Demolition Night is the culmination of the backlash and resistance to that movement which reflects the prominent racism and homophobia of the late 1970s much more than the dislike of disco as a genre.

To this day, the spirit of disco continues to live via house and electronic music, which derived from the disco genre and ironically originated in Chicago. Artists continue to pay homage to disco by incorporating it into their work. For example, LF SYSTEM sampled the 70s funk group Silk’s “I Can’t Stop (Turning You On)” for their house genre dance song “Afraid To Feel.” The music video for the song showcases people of the LGBTQ+ community and people of colour freely embracing their sexual and racial identities on the dance floor. Disco may not take on the same form as it did, but its liberating ideas ring louder than ever.

Leave a comment