Karina Hesselbo

Contributor

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

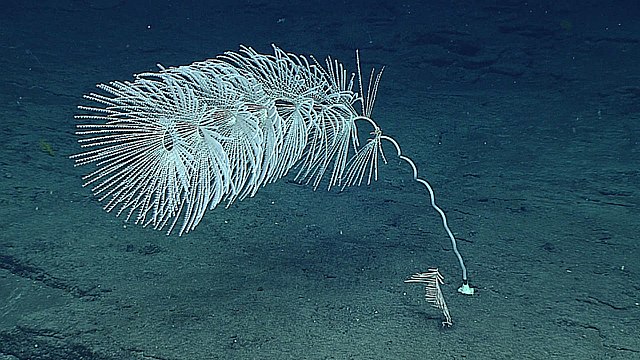

With crushing pressure and no light, it’s easy to imagine that the deep sea doesn’t hold much life. However, life doesn’t just exist down there, it thrives. There are thousands of species in the deep sea, ranging from giant, deep red jellyfish to tripod fish that “stand” on the seafloor using their fins, and from corals that range from the tropics to the Antarctic, to many more species we have yet to discover. However, while it’s easy to imagine that the deep sea is safe from human disturbance, that couldn’t be further from the truth. The Washington Post and The Deep Sea Conservation Coalition report that animals within the mariana trench, the deepest place in the entire ocean, have been contaminated with pollutants. Moreover, many deep sea fish, like the orange roughy, are threatened by overfishing. As with most biomes, even in the deep sea, we are at great risk of losing species before we even know they exist. One of the most pressing threats to the deep sea is deep sea mining.

We are at great risk of losing species before we even know they exist.

Deep sea mining is exactly what it sounds like. This will be done using vehicles that sweep the seabed for minerals and send the collected material to ships. Any unwanted sediments will be sent back into the ocean. Right now, deep sea mining is not yet taking place, though research on it is underway. Countries like Canada and Sweden have called for a halt on deep sea mining, while Norway has opened its waters to it.

Why are we mining the deep sea? Because we need minerals, like cobalt and manganese, that are used to create batteries, wind turbines, and solar panels. According to the World Resources Institute, these minerals are vital for renewable energy transition, and the deep sea contains loads of them deposited all over the seabed. For example, in the Clarion Clipperton zone, a targeted area, there are an estimated 21 billion tons of nodules there. But… could its ecosystems handle this mining? Probably not. Though deep sea mining has not begun, researchers are already concerned about its impacts. When these minerals are extracted, they release a plume of sediment that could stretch over many kilometres. When these sediments settle, they might harm filter-feeding shellfish and suffocate animals on the seafloor.

What’s more, deep-sea ecosystems are incredibly fragile. They run on a clock that’s much slower than other ecosystems’, with the species moving more slowly and maturing later. For example, while pacific bluefin tuna, a pelagic fish, can reach maturity in five years, the aforementioned orange roughy takes roughly 23 years to reach maturity. This slow-developing nature means that if a deep sea ecosystem is badly damaged, it could take many years to recover, or it may never recover at all. Another problem is that we know very little about this region, so we have little idea of how exactly deep sea mining will affect its ecosystems.

So, what can be done? Rather than mine the seabed for minerals, we could try recycling metals and improving batteries instead. In a report by the U.S. PIRG, the world threw away 62 million metric tonnes of e-waste in 2022, waste which–if recycled–could be given a second life. If we managed to reduce the amount of minerals that we throw away and increase their recycling, then we could achieve a circular economy where the demand for new materials is reduced. However, if we cannot obtain the metals necessary to provide a renewable energy transition through other means, then deep-sea mining must take place under strict rules to prevent ecological damage. The deep sea is a remote world, but one bustling with life, and it shouldn’t have to choke to death in our quest for minerals.

Leave a comment