Maya Jabbari

Staff writer

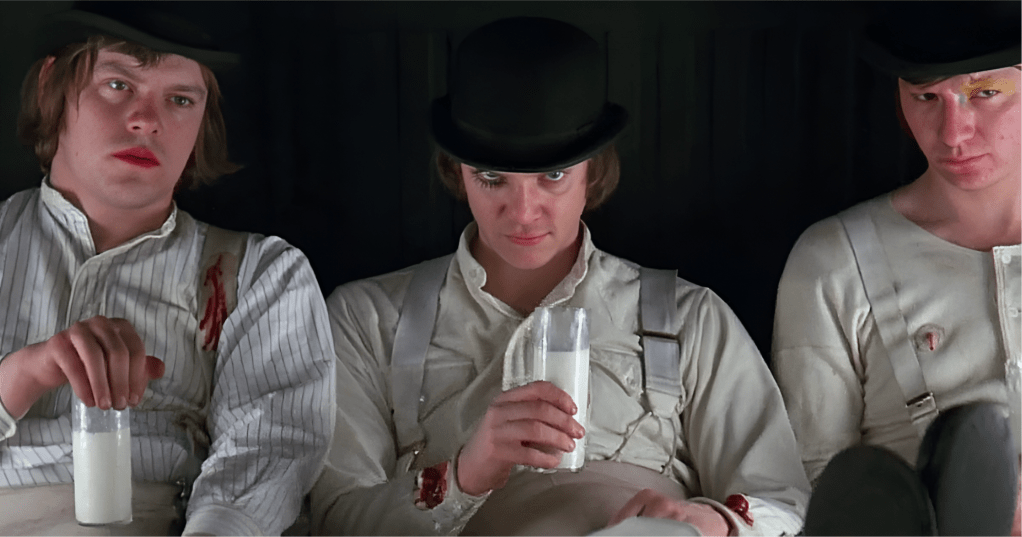

Photo Via The American Society of Cinematographers

As someone who has never had a liking for whole milk, even in my youth when it was served with almost every meal, and given to us at school in the little Québon boxes, I felt I was always forced to drink it. My parents would say my bones needed to be strong and I needed to grow and all that. I mean, of course, yes, milk is good for you! It’s the first food we consume as infants, and that directly makes it associated with growth, motherhood, and childhood. By extension, milk’s symbolism is also a direct representation of innocence and purity. I urge you to think of where you’ve seen milk. Maybe you’re picturing marketing campaigns, or, like me, maybe you’re picturing some movies…

Take Quentin Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds for example, in one of the film’s most tense scenes, we see SS Colonel Hans Landa visit a French dairy farmer who the Colonel suspects of hiding Jews during WWII. As Landa interrogates the farmer, he requests a glass of fresh milk. When that request is quickly realized, he lifts the glass, chuggs it, and the reminisce of the drink coats his lips as he praises the farmer for its quality. Tarantino juxtaposes our idea of milk as a wholesome drink with Landa’s sinister intentions.

Tarantino isn’t the first director to use milk to unnerve his audience. Stanley Kubrick employed a similar technique in his dystopian classic A Clockwork Orange. The film’s violent teenage protagonist and his gang frequent the Korova Milk Bar, where they drink drug-laced milk to prepare for their brutal crime sprees. The image of these young thugs downing milk creates a disturbing contrast between youthful innocence and extreme violence.

Another example of this subversion of milk is seen in more recent films like Get Out directed by Jordan Peele. In a pivotal scene that became quite popular, Rose casually eats Fruit Loops one by one while sipping a glass of milk through a straw as she searches for her next victim online. This scene makes the connection between innocence and violence even more prominent because of the addition of Fruit Loops, a childhood breakfast staple. We, as the audience, realize the true depths of Rose’s sociopathy.

So why does milk work so well as a symbol of hidden evil? It all comes down to the power of contrast. Milk represents everything these villains are not – pure, innocent, and nurturing. By consuming it, they’re essentially wearing a mask of normalcy that makes their true nature even more frightening. Think of the American Psycho monologue that Patrick Bateman delivers about his mask, “There is an idea of a Patrick Bateman, some kind of abstraction, but there is no real me. Only an entity, something illusory. And though I can hide my cold gaze, and you can shake my hand and feel flesh gripping yours and maybe you can even sense our lifestyles are probably comparable, I simply am not there.” This is the visual equivalent of a wolf in sheep’s clothing; a concept all of these directors are exploring.

To add, milk also serves to infantilize these characters in a disturbing way. Adult men drinking milk can come across as creepy or stunted. It proposes the idea that there’s something “off” about them, hinting at arrested development or a twisted worldview. When we see Landa drinking milk, a part of us can’t help but think “grown men shouldn’t drink milk like that, they shouldn’t chug it, it just seems weird” – which is exactly the unsettled reaction the filmmakers are going for.

The milk motif also ties into broader themes of corruption and tainted innocence that run through many of these films. This is especially seen in A Clockwork Orange, where the milk laced with drugs represents how society’s attempts to “cure” Alex ultimately poison his free will. And similarly, the milk in Get Out symbolizes how Rose’s outward wholesomeness masks her true monstrous nature.

By now, the sight of a villain drinking milk has become almost a cinematic shorthand for “this character is not quite right.” It’s a subtle but effective way for filmmakers to signal to the audience that something sinister lurks beneath the surface. So the next time you see a character on screen gulping down a glass of milk, pay attention – chances are, there’s more to them than meets the eye.

Leave a comment