Charlotte Renaud

Arts & Culture Editor

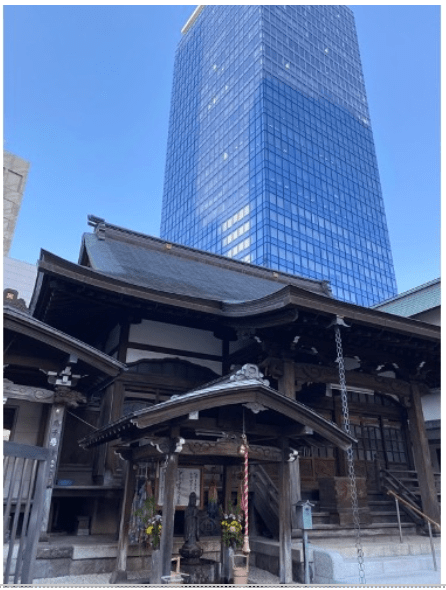

When we think of Japan, we are met with two very contrasting realities: a modern country forerunning advanced technologies that only exist in the western world’s wildest imaginations, and a country rich with culture and strong traditions tied to Buddhist, Shinto, and Confucianist religiosity. The birthplace of Nintendo and big discount stores like Don Quijote does not abandon tradition in its pursuit of modernity; instead, the country acts as proof that both modernity and tradition can coexist and may perhaps even be the ideal.

Traditions in Japan span from different festivities on holidays such as those during the New Year to customary tea ceremonies, all reminiscent of Shinto, Buddhism and Confucianism. The Stanford Program on International and Cross-Cultural Education explains that Shinto – Japan’s oldest religion – originated in a pre-literate society, before the sixth century C.E., and was thus transmitted through communal rituals. Shinto deities (kami), were believed to fill the natural world, taking the shape of uniquely beautiful trees, rivers, rocks, etc. By the seventh century, the Japanese had built shrines to commemorate the kami and act as a sacred place for rituals. To this day, shrines are still preserved and visited in the Japanese countryside as well as in big cities like Tokyo.

The Japanese were interested in the Chinese’ sophisticated ideologies presented in Buddhism. The Stanford Program on International and Cross-Cultural Education recounts that Buddhism arose in India in the sixth century B.C.E and then travelled through China and into Japan in the sixth century C.E. Influential Japanese Buddhist movements such as Zen were present by the thirteenth century C.E. The previously mentioned source also explains that Zen was attractive to the powerful samurai leaders for its discipline, frugal monastic traditions, and importance placed on meditation. By extension, the movement heavily influenced Japanese culture through its association to art, including monochrome ink painting and tea ceremonies.

A traditional and formal tea ceremony lasts several hours to properly serve a kaiseki course meal, thick tea, and thin tea. The prepared tea is served in a traditional tearoom with a tatami floor where both different kinds of tea are accompanied by sweets – the thick tea is served with moist treats such as omogashi, and the thin tea is accompanied by dry sweets like higashi. More than anything else, the practice prioritizes guests’ enjoyment and thus places great emphasis upon the host’s hospitality. Even today, tea ceremonies are still practiced and considered an important Japanese tradition. They are now often practiced as a hobby and are shortened to the simple enjoyment of the thin tea.

Tradition in Japan is far from forgotten; it is still honoured and celebrated frequently. Japanese traditions shine through during festivities such as those of the New Year where the Hatsumōde, the first worship of the year, takes place. The practice involves visiting a Shinto shrine or a temple to pray for good luck in the upcoming year. Lanterns and bold signs exclaiming “Happy New Year” are hung at local shrines. At the entrance, a chozu-ya, temizu-ya, or temizu-sha, depending on the shrine, is a water basin where people must purify themselves before entering the torii (the traditional gateway of a shrine). A common custom is to draw at random an omikuji (oracle written on paper) for the upcoming year and then tie it to a structure outside of the shrine for good luck.

Values found at the core of Japan’s traditions, such as hard work and continual improvement, advocate for the country’s modernity. In addition to Shinto and Zen, the Stanford Program on International and Cross-Cultural Education explains that the Confucian thought – founded in China by Confucius, whose teachings focused primarily on the cultivation of virtue – was equally as influential to Japanese culture. According to the same source, Confucianism’s filial piety (loyalty to one’s parents or ancestors), loyalty and dedication to duty and learning “helped the Japanese modernize rapidly in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.”

Japan’s technological advancement, aided by traditional values, is also backed up by Kaizen philosophy and government funding in education and technology. According to Investopedia, Kaizen serves as the foundation of the Japanese business philosophy by promoting continuous improvement. Powerful and successful Japanese businesses have employed this ideology, including Toyota. In fact, their site shares an article titled “How Kaizen can Power your Productivity” that defines the term from two words: Kai (improvement) and Zen (good). Therefore, it is no surprise that Japan is a forerunner when it comes to developing technologies.

The country is renowned for its abundance of convenience stores such as 7/11, Lawson, and Family Mart, which exceed customers’ basic necessities by much. These stores have many good quality food options including ramens, prepared dishes, onigiris, sushi rolls, coffees, vitamin juices, smoothies, pastries, bakeries, heated dumplings, curry croquettes… the options go on for aisles and aisles. Not only do these convenience stores have food, but they also have clothes, manga, newspapers, makeup, skincare products, materials for school, etc.

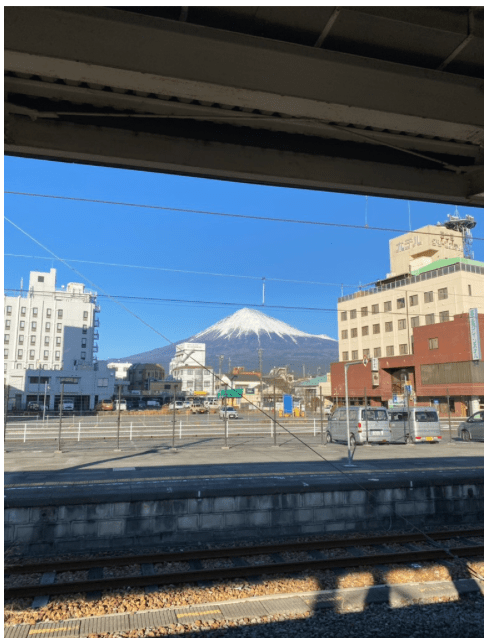

Unlike our limited transportation system in Montreal, Japan’s avant-garde train network is incredibly efficient and widespread. People can travel across the country simply by local train. Even remote towns are accessible via public transportation. Two hours spent using public transportation in Montreal won’t get you very far, whereas in Japan, it can get you as far as 450 km away. This is by virtue of Japan’s newest and fastest bullet train: the Shinkansen. Reaching up to 320 km an hour, the high-speed rail system has many networks throughout Japan that allow passengers to reach their destination in no time. For example, the Nozomi Shinkansen offers passengers direct access between Hiroshima and Tokyo, covering 816 kilometres in only 4 hours. In addition to trains, Japan has an abundance of metros, tramways, buses, taxis, and even sky trains such as the Chiba Urban Monorail.

Japan’s train network is also incredibly clean and organized – a kind of efficiency that is necessary during rush-hour. Many train stations and metros have barriers that prevent people from stepping onto the rails when the train is not there. Not only does this prevent any serious injuries, but it also prevents fallen objects from delaying the trains. Red and yellow lines on the ground in front of train entrances/exits illustrate where those embarking should stand and where those leaving the train should step out. Japan’s excellent organization is especially reflected in its transportation system.

Overall, Japan’s modernity has not been stunted by the country’s strong ties to tradition; on the contrary, it has been immensely pushed forward by them. We are victims of our own belief in the misconception that tradition and modernity are opponents. In reality, it is clear that strong roots are necessary for growth and that modernity is the fruit of tradition.

Photos By Charlotte Renaud

Leave a comment