Photo Via Reddit

Peggy Ethier

Videographer

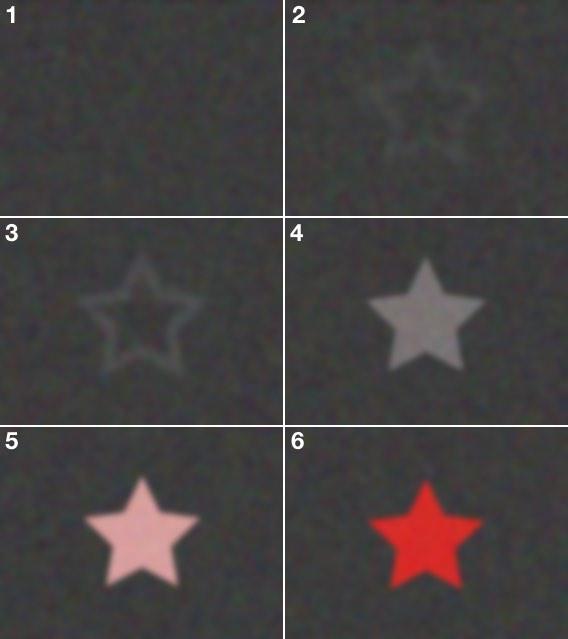

Let’s do a quick test. Close your eyes and imagine a red, five-pointed star. How clearly can you see it? Use the picture guide above to rate how well you imagined the star on a scale of 1 through 6. Most people score between a 3 and a 6, but if you scored closer to a 1, you might have Aphantasia– a condition where the mind’s eye remains blind.

People with Aphantasia, or aphants, cannot voluntarily visualise images in their mind’s eye, and often it comes as a shock that others might actually be able to do so. They have gone their whole lives assuming phrases like “picture this” were just metaphors. This is likely due to Aphantasia being a very recent discovery in the world of psychology.

Although there have been allusions to the condition dating back to Aristotle, it was not until 2003 that British neurologist Adam Zeman released the first case report of a man who, after suffering a stroke, complained of no longer having the ability to visualise in his thoughts. It then took Zeman another 12 years until 2015 to publish a proper study that defined the condition and coined the term Congenital Aphantasia. Aphantasia seems to be both a genetic condition (so having a parent who is an aphant greatly increases your odds of having it too) as well as a condition that can be acquired through brain trauma.

According to Psychology Today, Aphantasia affects around 4% of the global population, but many go their whole lives unaware, making it difficult to properly research. Although originally defined simply as a visual impairment of the mind, more recent reports offer theories that aphantasia might possibly be a memory disorder.

Andrea Blomkvist, a postdoctoral researcher, defined the condition in a July 2022 article for the journal of Mind & Language as the inability to recall any episodic memory. This means being unable to recall sensory information in your mind, including but not specific to visual, auditory, olfactory, gustatory, tactitory senses, which can greatly affect an aphant’s ability to remember autobiographical memories. The other elements of the memory and recall system, spatial and semantic memory, appear to allow aphants to remember the feeling of where an event took place as well as conceptualise information about the event; however, they are unable to recall exactly what it looks like to experience that event.

Take the memory of learning to ride a bike for the first time as an example. You might remember the general area of the street as well as other information like the weather and the colour of your bike, but you cannot actually visualise the beaming sun or the colour of your bike. You can cite these facts because you know they happened, but other than ‘knowing’ you are thinking of the event, you don’t see anything.

The range of experiences within Aphantasia is wide. Some aphants cannot recall any episodic information; however, for most, it is only visual, suggesting that the previous 2022 theory might be limited. Interestingly, around 15% of aphants are capable of recalling images when their eyes are open but are unable to visualise once they close them. These images are fleeting and often spontaneous, so they cannot control what they visualise. Other aphants can visualize when asleep. This shows the variation in human cognition: we all have some kind of mesh of the 5 senses in our imagination, except for a limited few, who have none.

Another approach to the condition considers it a little bit like a computer bandwidth issue. Some senses, like your visual imagination, take much more bandwidth to recall and so only people with full capacity can do so. Other people’s brains, who can only recall other senses and not visual, might have a reduced bandwidth, since those senses take up less space; when their brain is asleep and there is less to process, bandwidth opens up for them to be able to visualise, hence why they can see when they dream.

It is important to note that, despite growing interest in how Aphantasia broadens the scope of knowledge on the human brain, many hesitate to formally include it as a ‘disorder’ and would rather consider it a personal difference. This is a nuanced discussion with arguments such that plenty of people in history have lived never knowing they experience their thoughts differently, meanwhile other arguments emphasize that knowing the variations of the human ability to think might help treat and diagnose other illnesses and disorders. One thing that is agreed upon in the medical community is that there are many different layers to Aphantasia. As Joel Pearson, a neuroscientist at the University of New South Wales, says: “Aphantasia is part of the range of neural diversity [in humans].”

Most of us rarely consider that others might think differently than we do. But asking a friend to visualize a red star—or anything else—might just be an eye-opening (or eye-closing) conversation. Whether it’s a personal difference or a discovery, Aphantasia challenges our assumptions about what it means to “see” with the mind.

Leave a comment